As a deadly disease known as white nose syndome closes in on the province, Dave Critchley is on a mission

On a bright, bracing January morning in Alberta’s Rocky Mountains, Dave Critchley prepares to make his way to the bottom of a cave roughly 50 metres (164 feet) deep.

As a veteran caver and researcher of the bats that live in them, the Biological Sciences Technology instructor (Biological Sciences Technology – Renewable Resources ’98, Forest Technology ’99) has made hundreds of descents, one as deep as the Calgary Tower is tall. But few have been quite like this.

Before stepping off the edge of the cave’s threshold, a two-metre-wide hole at the centre of a depression among spindly spruce trees, he gently lowers the cargo tethered to his climbing harness. There’s a bag containing extra clothes, food, tools and scientific equipment. There’s also more than 150 pounds of nearly dead weight – me.

There’s also more than 150 pounds of nearly dead weight – me.

Half an hour earlier, I was fine. Critchley, myself, plus a former student of his and volunteer bat researcher Imogen Grant-Smith (Biological Sciences Technology – Renewable Resources ’16), had hiked briskly up an icy ridge, squinting at a postcard horizon of white-capped mountains. A small herd of mountain goats lazily yielded the path.

At the cave, as we emptied our bags of the ropes and climbing hardware with which we’d trust our lives, the expedition seemed manageable.

Then, after Grant-Smith descended and my turn came, it wasn’t manageable at all. Suddenly, my stomach tingled, my ears rang, the sky brightened unnaturally. I lied down in the snow. As we waited for my anxiety to subside, Critchley kindly shrugged off the episode as if it were a normal first-timer’s reaction. Finally, the feelings passed.

“We’ll go down in tandem,” said Critchley, clipping me to him so I could dangle lamely below as he expertly slid down the rope.

Hauling along a reporter is a small part of what the instructor will do for bats.

Hauling along a reporter is a small part of what the instructor will do for bats.

Since the early 2000s, Critchley has combined his love of subterranean environments and his fascination with one of Alberta’s least understood yet most ecologically important animals.

Once dismissed as creepy, the flying mammal is gaining appreciation as a fiercely efficient manager of agricultural and forestry pests.

The problem is, a large number of bats are on the verge of obliteration.

Recently, white nose syndrome has killed certain species in eastern North America with a fatality rate of up to 99% (which is why I am sworn to secrecy about this cave’s exact location, so amateur cavers won’t visit and possibly introduce the disease).

In 2016, it turned up in Washington state, creating new urgency around the mystery Critchley is playing a lead role in solving. No one knows where the vast majority of Alberta’s bats spend the winter, when the syndrome strikes.

Few people take this more seriously than Critchley. But even fewer would go as far as he does in calling it “pure enjoyment and fun – a beautiful marriage of passion and science.”

After touching down in the cave and detaching himself from me, he almost immediately begins scanning the frozen floor for any sign that bats have been here since his last visit more than a year ago.

An amicable introvert, Critchley seems to be at his happiest underground. On his hands and knees, he examines what looks like hairy beef jerky – a dried vole carcass – before being distracted by a beetle. “A coleoptera!” he shouts, turning his attention to watch the inch-long insect slowly crawl across cold grey limestone.

Then he gets on with the job of saving Alberta’s bats.

Mysterious ways

Mysterious ways

Judging from centuries of mythology, literature and pop culture, these animals haven’t had many advocates.

Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula, made bats and vampires kindred creatures but the Irish writer wasn’t the first to sully the mammal’s reputation. Medieval Europeans believed that bats served witches.

In fact, in 1332 in France, a woman was publicly burned after bats were noticed around her house at night. The Mayan god Camazotz was the “death bat” and Native American cultures saw bats as spies or traitors in the animal world. Even Batman is an oddity among superheroes, moody and reclusive, coming out only at night.

All this likely comes from bats’ mysterious nature. Science labels them “enigmatic microfauna”; that is, tiny and poorly understood. That’s particularly true in Alberta. “We have millions of bats and we know where only thousands are hibernating,” Critchley points out. “Where are the rest?”

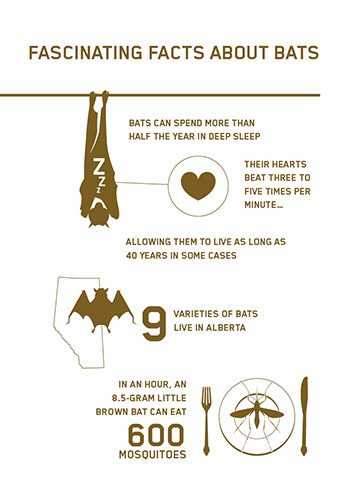

In Alberta, few bats migrate during cold months, instead hibernating in caves or mines (a.k.a. hibernacula when they’re bat homes). In perfect conditions – roughly zero degrees Celsius and 100 per cent humidity – bats can spend more than half the year asleep, their hearts beating three to five times per minute, allowing them to live as long as 40 years in some cases.

Some of these ideal locations are known, such as Cadomin cave, 50 kilometres south of Hinton. Recently, Critchley was part of an expedition that discovered a massive hibernaculum in the northern boreal forest, the largest known in Alberta outside the mountains. Besides Cadomin, the Rockies almost certainly contain many other winter bat homes – ones humans may never see.

“We have millions of bats and we know where only thousands are hibernating. Where are the rest?”

“All it takes is a small space for them to crawl through [that] opens up into a new chamber. We’d have no idea that they were there,” says Critchley, who since 2015 has been one of two coordinators for the Alberta chapter of BatCaver, a national project dedicated to revealing the seasonal comings and goings of bat populations in Western Canada.

Without that information, nothing can be done about white nose syndrome, which thrives in the cold and damp of hibernacula.

First noticed in a cave in New York in 2006, it’s caused by a fungus that grows on the nose and flesh of bats of the genus Myotis, the “mouse-eared” variety that accounts for more than half of the types of bats in Alberta.

It irritates them into waking to try to remove it, which burns fat stores, makes them hungry and forces them out into the barren winter landscape to search in vain for insects to eat. Ultimately, they starve. A 2012 estimate by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service put the death toll between 5.7 and 6.7 million. So far, it’s in 30 states and five provinces.

Where it turns up next is anybody’s guess.

“We’re talking about covering an enormous geography and it’s like [finding] a needle in a haystack,” says Justina Ray, president and senior scientist of Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, which oversees BatCaver. It’s even harder because of what the job demands of people.

Into the haystack

Into the haystack

Finding that “needle” takes a rare combination of talents.

Frequent expedition partner Greg Horne marvels at the breadth of Critchley’s skill set.

“It boggles my mind, the various topics,” says the Parks Canada resource conservation officer and BatCaver’s other Alberta coordinator.

Whether it’s rebuilding a chainsaw carbeurator or designing a study for sampling invertebrates, Critchley’s “got great attention to detail,” says Horne.

Dave Hobson (Forest Technology ’76) has been similarly impressed ever since Critchley, a former professional cave guide, first joined him in 2003 for the Cadomin bat count. “He’s an excellent caver,” says the senior wildlife biologist with Environment and Parks Alberta.

The future of the province’s bats may hinge on that. “We are not cavers,” says Ray of her small crew of scientists at the conservation society. “We could not do this without champions – one of whom is Dave.”

Last summer, Critchley’s skills were tested during a research expedition in the rugged Nahanni National Park Reserve in the Northwest Territories. Though more strenuous, that work serves as a kind of model for efforts in Alberta.

“We could not do this without champions – one of whom is Dave.”

With Horne, another Parks Canada researcher and a member of the Alberta Speleological Society, Critchley spent three weeks up north investigating potential hibernacula and summer roosts. Even by Critchley’s standards, it was gruelling.

Making day trips from a base camp, the team picked caves based on past reports from amateur cavers that mentioned bat sightings. Since then, however, forest fires have recast the terrain as a carpet of aspen saplings.

“It’s like we were swimming through the forest: put your arms forward, push the trees back, step – we’re doing this for hours,” says Critchley. At times, they travelled just 300 or 400 metres an hour, estimates Horne. It never bothered Critchley.

“Dave will soldier on with a good level of positive thinking and enthusiasm that often can make the best of a bad situation,” says Horne. “If you’ve got good spirits and good morale, it rubs off on everybody.”

Perseverance paid off. The team found signs of bats, if not bats themselves, in dozens of caves.

A healthy hibernaculum can be defined by seemingly unhealthy things.

A healthy hibernaculum can be defined by seemingly unhealthy things.

Guano, or tiny pellets of bat excrement, is one sign of occupation (and a way to identify species, through DNA).

It was on the walls and floor of most caves Critchley visited in Nahanni. Dead bats are another good sign – as long as their mummified carcasses date over a long period of time, sometimes centuries, showing long-term habitation.

“You don’t want to see a thousand bats on the floor, all of them covered in fungus,” Critchley says.

Upon leaving a cave, they installed a “roost logger.” The size of a small plastic tool box, it records the lives of bats when humans aren’t there. The machine records sounds that suggest population size and, from the audio frequency of their calls, can indicate species.

A healthy hibernaculum can be defined by seemingly unhealthy things.

Nearby, they set up temperature and humidity recorders. Just as in Alberta, the idea is to find where bats are when they’re most vulnerable to white nose syndrome – identifying, essentially, future treatment sites.

Considering Ray’s “haystack” comparison, and the possibility that the syndrome lurks along the B.C. border, the cavers’ success seems unlikely. Nahanni alone is 30,000 square kilometres; Alberta is roughly 640,000. That’s a lot of territory to cover for the handful of volunteer “citizen scientists” coordinated by Critchley and Horne through BatCaver.

But, just like facing that forest of aspen between him and the next cave, Critchley doesn’t dwell on the negative. He just heads toward the solution. “If you don’t know where these guys are, you can’t protect them,” he says.

Not so creepy anymore

Not so creepy anymore

Another type of positive attitude is also playing in Alberta bats’ favour: people aren’t so freaked out by them anymore.

As a kid, Hobson would remove bats from local buildings and safely relocate them. Today, he understands that the economic value of the work they do is worth billions.

The province’s agriculture and forestry industry, which hungry bats protect from bugs, is worth roughly $5.3 billion a year. Then there are mosquitoes. In an hour, an 8.5-gram Little Brown bat can eat 600.

“I’ve seen a real shift in attitude toward bats,” says Hobson.

“Now if somebody calls, they’re more likely to ask how they can get them out of their houses but they don’t want to kill them. They still want bats in their yard, eating mosquitoes.”

But the true tipping point for bats in Alberta may be the growing number of people interested in contributing to the cause – some of them inspired by Critchley.

One of the key things Erin Low (Biological Sciences Technology – Environmental Sciences ’14) learned from her former instructor was “a general respect for all things” in nature and their interconnectedness. “He really tied everything together.”

“I’ve seen a real shift in attitude toward bats.”

Following courses in which Critchley discussed bats and field work, Low found employment doing ecological surveys for industry, determining things like bird and bat species in areas slated for development.

The work helped make it clear that “there’s so much missing information about bats. It’s a void in what we know about a very important wildlife species in Alberta.” Today, she’s the Edmonton region coordinator for the Alberta Community Bat Program.

As she pursues a biology degree, Low hopes her future career also involves conserving bat species. In fact, she’s taken Critchley up on an offer to literally show her the ropes. “I can be involved in active research in the province and develop a skill set that I couldn’t develop on my own.”

Zen and the science of bat conservation

Zen and the science of bat conservation

For Critchley, that skill set brings an unexpected benefit. In that cave somewhere in the Rocky Mountains, he’s cut off from the world above and engaged, zen-like, with his unique surroundings.

These trips may be about the bats and the work required for their conservation, but going underground gives Critchley a special kind of peace.

After having fretted about it at first, I see why.

Inside, I find a comforting space, enveloping and protective, surprisingly warm the deeper you descend.

Elements of it command your attention: the walls’ bubbled surfaces; a fine airborne grit illuminated by a headlamp and coating the teeth with a mild sour taste; a live mosquito, unaware of the season.

Time seems to operate differently. We eventually climb out after what felt like an hour or two. It turned out to be about six.

Then there’s the silence, broken by the softest sounds. Critchley’s ears catch the almost inaudible sound of my scribbling on a notepad. “Every time I hear your pencil,” he says, “I look around and wonder where the bats are.”

It turns out that my squeaky writing sounds like their vocalizations.

All of this, I can’t help but think, must make this work bearable. This isn’t science for the faint of heart, encompassing careful planning, hard travelling, and climbing that can require thick thighs, square shoulders and ropy forearms. This is to say nothing of the challenge of gathering data.

This isn’t science for the faint of heart.

But Critchley finds it refreshing. A weekend with bats recharges him for a week in the classroom.

It may even make it easier to stick with the enormous task (and responsibility) of trying to save a vital species without losing hope. Hard physical labour has a tendency to keep you in the moment, undistracted. For Alberta’s bats, that moment may be all that matters right now.

When white nose syndrome finally arrives in the province and it’s time to treat bats at hibernacula, the job will likely fall to someone other than Critchley. In fact, how treatment will happen is unknown.

In the U.S., some bats eat fruit that could be inoculated with a cure. You can’t inoculate an Alberta mosquito, points out Critchley.

But he’s not losing time thinking about that. Instead, he’s focused on trying to uncover the mystery that needs solving. Critchley knows that the only way they’re ever going to be able to shine a light on it all is to keep searching, day after day, hike after hike, in those places where the light doesn’t shine.