90,000 tonnes of fly ash ends up in Alberta landfills annually

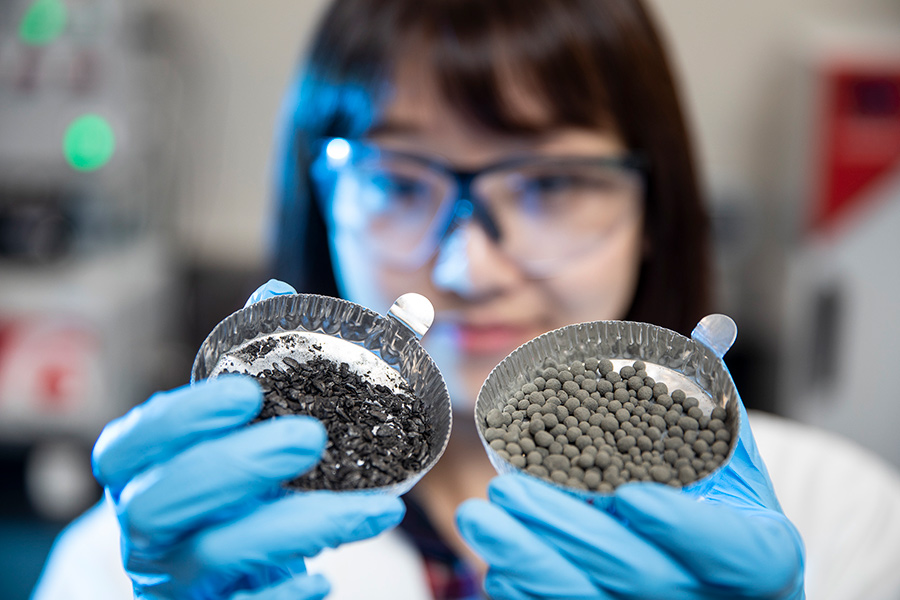

The Ziploc bag in Dr. Jean Cai’s tidy lab at NAIT is filled with what look like peppercorns. But these small, round pellets hold great promise as a new, low-cost and environmentally safe way to remove noxious hydrogen sulphide at natural gas wellheads, water treatment plants and pulp mills.

Made from fly ash – a waste product from pulp and paper mills – the pellets are proving to be extremely effective at absorbing and filtering hydrogen sulphide, the rotten-egg-smelling gas produced in many industrial processes that, in high concentrations, is poisonous, corrosive and flammable.

In the lab, Cai and her team have found the fly ash pellets are 10 times more effective at absorbing hydrogen sulphide than the activated carbons filters currently used by industry.

“We’ve found it performs even better than the commercial products,” says Cai, who has been working on the project since March, 2018. “Rather than just dump it, we thought, ‘why don’t we recycle it and find another way to use it?’”

Turning waste into cleaner air

The added bonus? The fly ash is not only free, it’s a voluminous waste product pulp mills must pay to haul, landfill, monitor and water to keep moist so it doesn’t catch fire. The ash is produced by burning bark and other unusable plant material to help power the mills’ operations.

In Alberta, about 90,000 tonnes of fly ash ends up in a landfill every year – so much that the province has stopped issuing landfill permits for the material.

Dr. Paolo Mussone, NAIT’s applied bio/nanotechnology industrial research chair, first approached the pulp mills with the idea of potentially using the high-carbon fly ash as a scrubber and deodorizer for the smelly plants.

“It worked so much better than what has been used for some time.”

Mussone had seen research that showed ash from coal combustion could absorb hydrogen sulphide, and since coal is a densified form of wood, he hypothesized that fly ash would also work.

Mussone had seen research that showed ash from coal combustion could absorb hydrogen sulphide, and since coal is a densified form of wood, he hypothesized that fly ash would also work.

Industry jumped at the opportunity to turn their waste into a resource with a consortium of companies co-funding his research with Alberta Innovates. Now Mussone and Cai are working with Mercer International in Peace River, International Paper in Grande Prairie and Alberta Pacific Forest Industries (Alpac) in Boyle, Alberta to validate and test their research findings.

So far the results have surprised even him.

“It worked so much better than what has been used for some time.”

Mussone says he was so taken with their findings, he sent samples to be validated at the only other lab in North America that performs these tests. Their results were virtually the same.

Soaking up odours downwind of industry

The fly ash is particularly effective at treating hydrogen sulphide for two reasons, says Cai. First, it physically absorbs the liquid gas. Second, it contains metal oxides, which react chemically with the gas to help with the absorption.

Researchers at NAIT’s Centre for Boreal Research, who have expertise in producing seed pellets for their reforestation work, helped on the project by mixing the papery grey ash with water and white glue, then turning it into pellets.

The machinery that tests the absorption capabilities of their samples was built by their colleagues at NAIT’s Centre for Sensors and System Integration.

Fly ash is 10 times more effective than existing filters

The pellets could potentially be used in air filters as deodorizers for pulp mills or water treatment plants, where bacterial fermentation also creates smelly, sulphur-based compounds.

They could also be used to remove hydrogen sulphide and potentially, carbon dioxide, from sour gas. Currently, industry uses solvents called amines to remove these gases in a process known as sweetening. But the solvents must be hauled away and disposed of, making them expensive to use.

The researchers hope to some day flow the natural gas through a bed of pellets to absorb the contaminants. They’re also looking at ways to regenerate pellets that have absorbed their fill of hydrogen sulphide, using air flow and heat.

A local company that manufactures industrial air purification equipment has agreed to build a prototype unit and field test the pellets.

Mussone says the next phase of their research involves looking more closely at the chemistry of fly ash to find out why it works so well. Ultimately, they’d like to produce a pellet that would absorb hydrogen sulphide effectively, inexpensively and consistently, that could be regenerated and reused, and would produce only a small amount of elemental sulphur as a stable, easy-to-remove waste product.