The unique properties of clays make them suitable for a wide variety of applications

The discovery and use of clays dates back to 30,000 years ago, making clays one of the oldest materials used in society. Clays are naturally occurring materials that were first used to make pottery and are now used abundantly in the manufacturing of goods, including ceramics, cosmetics and building materials. Clays also play an important role in the “terroir,” the features a wine develops based on where the grapes are grown.

Clay has unique properties that are useful in industries ranging from manufacturing to construction. But these properties can also pose a challenge in managing mine waste.

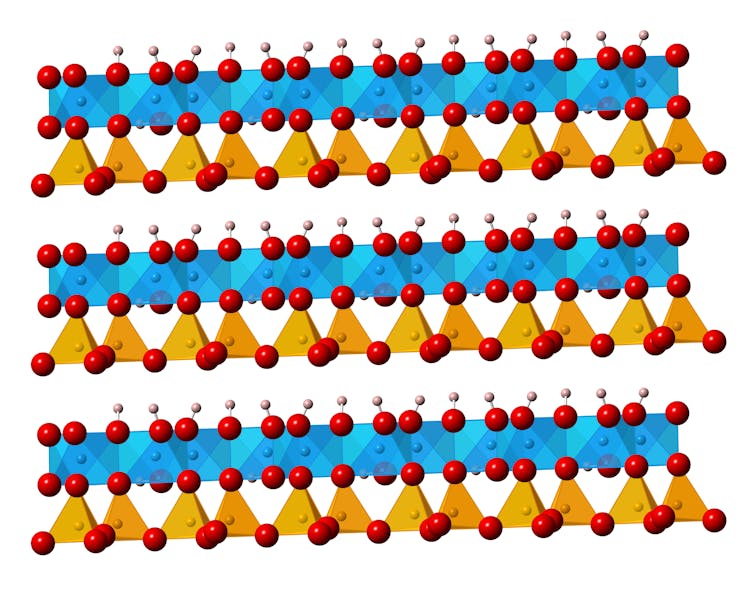

Clays and clay minerals are tiny particles with a unique plate-like structure less than two microns in size (for comparison, the average thickness of a strand of human hair is about 70 microns). The small size of clay minerals and their distinct structure give them unique properties, and different types of clay minerals can exhibit diverse characteristics.

Properties of clays

There are four main groups of clay mineral: kaolinite, illite, vermiculite and smectite.

Clay minerals are classified based on the arrangement of their molecules and layers. (Shutterstock)

Clay minerals are classified based on the arrangement of their molecules and layers. (Shutterstock)

Smectite clays for example, have the greatest ability to swell, often expanding several times their initial volume. Bentonite clay, a smectite, can swell up to 18 times its initial volume by taking water into its interlayer, the distance between two layers of clays. This property makes it useful as a spill absorbent, but also means that it is very difficult to remove water from clay in dewatering processes, as in the case of mine waste management.

In contrast, kaolin, or china clay, does not swell and has low permeability, making it preferable for producing porcelain or improving the printability of paper.

Clays also develop plasticity when wet, giving them the ability to stretch without breaking or tearing — a critical property for pottery sculpting. The drying and firing processes cause the water molecules to escape from between the clay sheets, and irreversibly changing the chemical structure of the clays, turning the piece into a hard and long-lasting pottery piece.

Clay and wine

Vineyard owners use their knowledge of clay content in the soil to help them make decisions about planting and irrigation so that they can improve the quality of the wine they produce. The soil composition in vineyards influences the drainage levels and the uptake of minerals and nutrients for the roots. Sandy soils are great for drainage, and clays, which have a net negative charge, help retain positively charged nutrients including calcium, magnesium and potassium.

The composition of the soil and clays that grapes are grown in can affect the taste of the wine. Vineyard owners can use this knowledge to produce specific notes. (Shutterstock)

The composition of the soil and clays that grapes are grown in can affect the taste of the wine. Vineyard owners can use this knowledge to produce specific notes. (Shutterstock)

Clays also hold water quite well, which can be helpful in dry climates to keep the soil cooler and wetter. Certain vine varieties produce the best results in a particular soil type. For example, clay soils tend to produce bold and muscular red wines like sangiovese and merlot and white wines like chardonnay.

Clay in mine waste

While clays can be valuable materials in certain industrial processes, they can also cause problems in mine waste management. For example, oil sands tailings — produced from the surface mining of oil sands — consist of a mixture of water, sand, fine particles, clays and residual bitumen.

These tailings are stored in ponds, where the heavier sands settle quickly to the bottom and the fine particles and clays remain suspended. The water-loving nature of clays means that a lot of water is trapped in the tailings, making consolidation and subsequent reclamation very challenging.

As of 2018, there are more than 1.2 trillion litres of fluid tailings accumulated in these ponds in Alberta.

Bitumen, water, sand and grass at a mine’s tailings pond, where the fine particles and clays gradually settle. Oil sands tailings are waste materials produced from extracting bitumen from the Alberta oil sands. (Shutterstock)

Bitumen, water, sand and grass at a mine’s tailings pond, where the fine particles and clays gradually settle. Oil sands tailings are waste materials produced from extracting bitumen from the Alberta oil sands. (Shutterstock)

This fluid tailings problem is not exclusive to oil sands as all forms of mining — such as copper, potash and diamond — produce tailings. As the global production of minerals and metals continue to rise, so does the production of tailings.

Clay measurement methods will become increasingly important to monitor and optimize tailings management strategies.

Treatment methods

Many tailings treatment solutions modify clay properties to accelerate dewatering and consolidation, and so understanding the clays present is critical for any treatment methods to work.

Clays can be characterized based on particle size, mineral type, surface area, cation exchange capacity, plasticity and flow behaviour. In a laboratory setting used in the oil sands industry for decades, methylene blue dye can help determine some of these important properties.

NAIT researchers are integrating robotics, sensors and optical systems to automate the methylene blue index laboratory method. (Author provided)

NAIT researchers are integrating robotics, sensors and optical systems to automate the methylene blue index laboratory method. (Author provided)

NAIT and its partners are developing an automated clay analyzer based on the methylene blue index method that would make it possible for in-field clay measurement. This would optimize treatment processes, translating to cost savings and faster reclamation of the tailings ponds.

From helping to create reclaimable tailings to producing a bottle of quality wine, advances in clay measurement can bring many economic and environmental benefits.

Jason Ng is a research associate, oil sands sustainability and Andrea Sedgwick is applied research chair, oil sands sustainability at NAIT. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Banner image: Jef Wodniack/iStockphoto.com.