Dr. Ray Rajotte built not just medical gadgets, but a community of problem-solvers

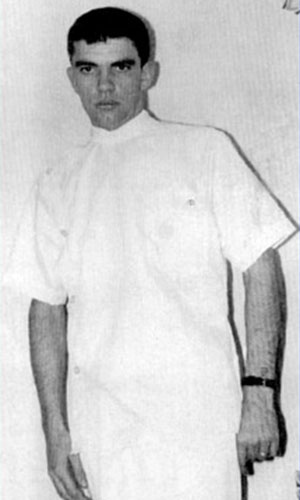

In the late 1960s, Dr. Ray Rajotte was sitting in the Edmonton General Hospital, flipping through a magazine. He was in his mid-20s and working as an X-ray tech. Though he was years from achieving the doctorate that would add that prefix to his name, the magazine was about to point him in that direction. With his patient yet to arrive for a scan, he paused on a page.

An article read, “Biomedical engineer: the way of the future,” recalls Rajotte, a member of NAIT’s first graduating class of Medical X-Ray Technology (1965, Honorary Degree '21). “I said, ‘Well, maybe I’ll become a biomedical engineer.’”

It was that kind of curiosity and openness to new opportunities that led Rajotte to his job at the Edmonton General in the first place.

It was that kind of curiosity and openness to new opportunities that led Rajotte to his job at the Edmonton General in the first place.

Not long before, he was a farm boy from Wainwright, Alberta. He didn’t dislike it, but he’d seen how hard it was on his dad, who worked all summer before spending winters as a railway labourer. When Rajotte learned of a relative who’d become an X-ray tech, he thought, “Maybe this would be an interesting career path.”

Rajotte didn’t really know what a biomedical engineer was. But he knew it meant learning and growth. And it was probably a way into research, which he’d enjoyed when he’d helped a doctor with angiography, using X-ray technology to study blood flow in the heart.

Little did Rajotte know that continuing to follow through on his curiosities would not only define the rest of his life, but make him a pioneer in the study of medicine.

Today, in the year of the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin in Toronto, in 1921, the University of Alberta professor emeritus is recognized as a global leader in type 1 diabetes research that has positioned the world closer than ever to a cure for a disease that affects roughly 9 million people.

Getting to that point, however, would require more than curiosity and openness. Rajotte would come to embrace roles as collaborator, coordinator and mentor. Keeping with his roots on the farm, and the hands-on nature of his NAIT education, he’d also be a machinist, inventor and builder of everything from lab equipment to careers to research institutes.

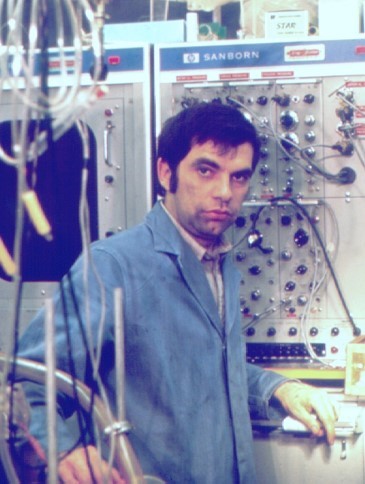

When he contacted the University of Alberta after that day in the waiting room, Rajotte found no such program there. He enrolled as an electrical engineer instead, ultimately graduating as what he is told was the university’s first designated biomedical engineer. “I took all my options in medicine,” he says. “I took the core courses, like calculus and basic engineering, but then I took biochemistry, physiology, anatomy.

“I made my own program.”

The exploding kidney

Kidneys have nothing to do with the causes of diabetes, but they are what started Rajotte’s research into the disease.

Kidneys have nothing to do with the causes of diabetes, but they are what started Rajotte’s research into the disease.

In fact, one kidney in particular, from a larger animal, would refocus Rajotte’s attention on how he might put his novel training to work in finding a treatment. One day, in the early 1970s, that kidney exploded in front of him.

Following his undergraduate studies, Rajotte started as a grad student with a researcher interested in cryopreservation, or freezing organs and tissues for future transplantation. The freezing went fine. Rajotte devised a method to cool a kidney to -200 C without harming it.

Thawing was different.

Rajotte thought to warm the kidney using a microwave, a technology then being researched in the engineering department, which he was still part of.

“I put it in the microwave and started to thaw the kidney from those low temperatures,” he says. “Within 60 seconds, the kidney blew up.”

“Within 60 seconds, the kidney blew up.”

Eventually, Rajotte tweaked his methods to thaw the organs intact, but they worked poorly upon transplantation. When he came across a paper out of St. Louis, where researchers had isolated rodent islets, the tiny pancreatic structures that secrete insulin to regulate blood glucose, he decided to repurpose his freezing procedure.

Functioning islets, Rajotte knew, could potentially rectify type 1 diabetes, brought on when these mini-organs failed, allowing blood glucose to go unchecked. What if functioning ones could be frozen for future transplant like a kidney? So he learned to isolate islets from rat pancreases, cryopreserve them and use them to cure sick animals.

Rajotte had no personal motivation to address diabetes. No one in his family suffered from it. But he knew how devastating it was (and continues to be), decreasing quality of life and ultimately shortening it, largely because of complications brought on by relentless blood glucose fluctuations, including blindness, kidney disease and nerve damage.

For his postdoctoral training, Rajotte travelled to research labs in the U.S. to learn more from leaders in the field of islet isolation. When he finished and returned to Edmonton, he became an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery and Medicine and set up a lab in the U of A’s Surgical Medical Research Institute (SMRI).

One of his first projects was to freeze rat islets in Edmonton and send them to St. Louis, where researchers thawed and transplanted them into compromised animals. The islets from Edmonton, shipped almost 3,000 kilometres, normalized them.

It was a global first. And it set Rajotte’s focus firmly on the field of islet isolation and transplantation.

Thereafter, his lab perfected the technique with larger mammals, namely dogs, using isolated islets to successfully cure diabetic animals.

“But then,” says Rajotte, “we were starting to think human.”

Filling the gaps

One of Rajotte’s strengths was as a builder, literally and figuratively.

As to the former, he had his own machine shop in the SMRI where he could cobble together a tool for one job or another that no one had done before, or do it better.

“Whenever I needed something, I had a lathe, a milling machine, welders, et cetera,” says Rajotte. “I was handy enough that I could do some fabrication.” He’d build a working prototype and then have his old friends in the Engineering department refine it. These prototypes included his novel islet isolation technology.

“He built a machine that, in the simplest terms, purées pancreases,” says Don Oborowsky (Carpenter ’69), whose son was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at around 12 years old.

A successful Edmonton businessperson, Oborowsky was a founding member of the local chapter of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, then was the central figure in the creation of the Alberta Diabetes Foundation (ADF). Throughout the late 1980s and ’90s, ADF would help fund much of Rajotte’s work in islet isolation and transplantation, and set the stage for advancements that would come from it.

“[Rajotte] developed this thing that took pancreas and islet cells and separated them,” says Oborowsky.

Rosemarie Henley (Medical Transcription ’76), Rajotte’s executive assistant of several decades, recalls a room full of surplus equipment that her boss picked up from hospitals to help support the SMRI, which he’d later direct in addition to conducting his own research.

“He would just jury rigg stuff. He was that kind of guy.”

“If somebody needed a piece of equipment, he would fix it up,” says Henley. “He would just jury rigg stuff. He was that kind of guy.”

But Rajotte was also the kind of guy who recognized that he could not do it all.

As he recognized gaps in his research and knowledge, he worked to fill both with people. Many were lab techs from NAIT. Rajotte kept ties with George Allan, assistant head of Biological Sciences Technology, to recruit his best students. They transitioned seamlessly into the labs, recalls Henley, who helped conduct those talent searches. Many of them remain there today, Rajotte points out.

For similar reasons, Rajotte also took a keen interest in the progress and growth of graduate students.

One was Dr. Gina Rayat, who took over as director of the SMRI when Rajotte stepped down in 2011 (she also initiated the call to give the centre its current name: the Ray Rajotte Surgical Medical Research Institute).

One was Dr. Gina Rayat, who took over as director of the SMRI when Rajotte stepped down in 2011 (she also initiated the call to give the centre its current name: the Ray Rajotte Surgical Medical Research Institute).

“He had a plan for me,” says Rayat, whose work now involves investigating pig islet transplantation into humans and anti-rejection strategies. Rajotte arranged for her to join a top lab in Denver for postdoctoral training in immunology, which would come into play in preventing rejection of transplanted islets. He’d call her regularly to check in.

“I treat him like a father-like figure,” Rayat says. She felt Rajotte genuinely cared about her and her career.

Oborowsky saw that side of Rajotte too, particularly in the style of leadership he showed when the two spearheaded the creation of the Alberta Diabetes Institute, opened in 2007 at the University of Alberta. It’s now the largest standalone institute of its kind in North America, and the research base for roughly 50 scientists and 400 support staff pursuing cures for type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

“He believed that in order to be successful you had to have everyone happy and successful around the table,” says Oborowsky.

Rajotte knew that the quality of life of millions of people hinged upon that happiness and success. Those calls to Rayat in Denver served a dual purpose, as he knew other institutes were eager to lure her away. “Remember,” Rayat remembers him telling her, “you’re coming back to Edmonton. Make sure that you are productive!”

This was characteristic of a person who refused to lose sight of his vision of the future, in which his work might lead to a successful treatment of diabetes. The present, like research itself, was like a series of variables over which he hoped to have some influence. The way Henley remembers it, there were many such variables.

“I started work at 7:30 in the morning and Dr. Rajotte was already there,” she says. “I barely had time to get myself assembled and he was already firing off questions.”

He wanted reminders to do things, to meet with people, to be places. “We had sticky notes everywhere,” says Henley.

It was stressful, but “in a good way,” she adds. “He was so busy. We were just so busy all the time.”

The path to the Edmonton Protocol

Rajotte was busy building toward what would become known worldwide as the Edmonton Protocol.

After starting to think “human,” he formed and directed the Islet Transplantation Group in 1982. For several years, they refined the process to isolate human islets, then they made history. In 1989, the group performed Canada’s first transplant of human islets, injecting them into a patient’s liver where they integrated into small blood vessels and began to function.

The procedure showed promise but was far from perfect, with a success rate of only 8%. What’s more, the pause in daily insulin injections wasn’t permanent; patients’ diabetes would inevitably return. So Rajotte began to build the team further, seeking out more clinical specialists.

These included Dr. James Shapiro, who’d come from the U.K. to the U of A to do a transplantation fellowship and doctorate in experimental surgery under Dr. Norm Kneteman and Rajotte. Shapiro, who would lead the next iteration of Rajotte’s group, began looking at anti-rejection drugs used during the islet transplant process, finding that some were toxic to the islets themselves.

Changes to immunosuppression methods, among other adjustments, led to a 100% success rate, with patients stopping their daily insulin injections.

“That became known as the Edmonton Protocol,” says Rajotte.

“That became known as the Edmonton Protocol,” says Rajotte.

It would also become “the standard of care,” he adds, with hundreds of people undergoing the procedure around the world within the few years after it was documented in the New England Medical Journal in 2000. The cost of the protocol was covered by Alberta Health Services, increasing access in the province.

The success would make Rajotte and the islet team key characters in the ongoing story of the battle against diabetes.

Whereas Frederick Banting, Charles Best, J.B. Collip and J.J.R. Macleod discovered insulin, the Edmonton team discovered how to reinstate its production in those with diabetes. But the Edmonton Protocol was not the end of the story.

But the Edmonton Protocol was not the end of the story.

Some patients would remain insulin-independent for many years. About 50%, however, would need to resume insulin injections, though less than they needed before the procedure. Importantly, Rajotte points out, they did not develop the later complications of diabetes.

The impact of the Edmonton Protocol was obvious to Oborowsky.

Sixty years ago, when he was a kid, Oborowsky watched a classmate struggle with the disease. He’d inject himself with insulin using a large syringe that he’d clean in a bathroom sink using well water. It was the kind of needle Oborowsky’s dad used to vaccinate cattle. Years later, he’d see progress in treatment with his son, who was able to keep playing A-level minor hockey. Then came the protocol.

“We don’t have a cure yet,” says Oborowsky. “But it’s a lot better.”

If this isn’t the end, there’s a chance it’s the start of a final, though likely lengthy, chapter. “The researchers learned a lot through that protocol,” Oborowsky adds. “It allows them to advance to another level.”

The beginning of the end?

Rajotte still gets up at about 5 a.m. everyday. “I’ve never been able to sleep very well,” he says. “That’s what I did when I was working – I always started early. Creature of habit, I guess.”

Rajotte, now a member of the Order of Canada and the Alberta Order of Excellence, is retired in theory but not practice. He sits on the board of Alberta Diabetes Foundation and continues to help with fundraising efforts. And, as professor emeritus, he and Rayat remain collaborators.

“We still continue talking about research,” she says. “People still seek his advice, our chair [in the Department of Surgery] consults with him, I consult with him.”

He laid a foundation upon which others are now building. “Without Dr. Rajotte,” Rayat adds, “there would not be a human islet transplantation program, [or] human islet isolation. He started it all.”

Oborowsky would agree. “Dr. Rajotte was a leader in diabetes research,” he says. “Without people like Ray we might be 10, 20 years behind.” But now, he adds, “I think we’re onto something new again.”

That is what Rajotte expected. Throughout his research, “I surrounded myself with outstanding students who were experts in certain areas and that’s how we were able to move the field forward,” he says. “It was very much a team effort.”

Today, the team that has succeeded him is taking the field in a direction Rajotte couldn’t, because what was once theoretical is only now becoming possible. The key to a reliable treatment, Rajotte feels, is an unlimited supply of islets. There are not enough available today from human donors.

“Without people like Ray we might be 10, 20 years behind.”

Rajotte sees a promising solution coming from teams led by Shapiro, now the Canada Research Chair in Transplantation Surgery and Regenerative Medicine, and Rajotte’s former tech-turned-grad student Dr. Greg Korbutt (Biological Sciences Technology – Laboratory & Research ’82), now scientific director of the Alberta Cell Therapy Manufacturing Facility. They’re part of a project investigating the transformation of a patient’s own red blood cells into stem cells that can in turn be transformed into insulin-producing cells. This would eliminate the need for both donors and anti-rejection drugs.

“I think that’s going to be the future,” says Rajotte.

It will take time. “Research is a progression,” he adds. It moves in stages separated by unforeseen challenges. It took 10 years for Rajotte and his group to move from curing rats to curing dogs. It took 10 more to get to humans.

Looking back on that, and at where it might lead, he’s willing to consider his work in islet isolation as being the kind that, in another 100 years, the world will see as having been essential to solving the problem of diabetes. “The ability to isolate pure islets has allowed a lot of different ways in which people can carry out research,” Rajotte says.

But he doesn’t see islets as the sum total of his impact. “My other satisfaction over 40 years as an academic is that I had the good fortune to supervise some outstanding students, graduate students, surgical fellows, research fellows and a dedicated group of technicians from NAIT. And each one contributed to a certain area to improve the way we isolate or transplant islets.

“It was great for me to see my graduate students develop into independent world-class leaders in the field of islet transplantation,” he says. “And they’re all over the world.”

Many of them remain in Edmonton, from which Rosemarie Henley believes a cure will ultimately come. Over the years, she could look up from that sea of sticky notes and see the community Rajotte was building.

“I think that they are just unlocking all of the clues and one day it will click,” she says. By they she means the people Rajotte brought in to fill the gaps, and those who later joined them, all of whom now continue to build upon a foundation laid decades earlier.

“Part of him, his legacy,” Henley says, “is in these people.”

Originally published Dec. 29, 2021