Award-winning project addresses lack of connectivity abroad and in Canada

Maybe your day starts something like this. Get up, turn on the bathroom tap, brush your teeth. Head into the kitchen, flip on the light. Turn on your phone to check the news or sign in on a laptop to start your day at school or work.

Now, turn off the water supply. Cut the power. Break the internet connection.

Getting by without the first two is incredibly tough. But the pandemic has elevated the internet to a similar rank, essential to keeping us working, in touch, and to simply carry on with daily life. Consider school closures, says Murray Lytle, past executive director of Light up the World (LUTW), a non-profit organization dedicated to providing access to energy in remote areas of the developing world.

In some places, education was essentially switched off when the virus made it too dangerous to congregate, “because there is no internet,” Lytle points out. Today, nearly 3 billion people live in those regions, most – but not all – in developing countries. Besides being cut off from education, going without internet means a lack of access of the sort that many of us might take as much for granted as a glass of water or a bright light bulb.

Ensure that connectivity, says Lytle, and “there are big communications possibilities.”

That’s why he reached out to NAIT, as LUTW has done in the past, to tap the creativity and ingenuity of students. The organization wanted a system to bring the internet to places disadvantaged without it, and to ensure the system could function entirely off grid.

The result was a plan that topped the efforts of students from three other Alberta post-secondary institutes and was named the 2020-21 capstone project of the year by the Association of Science and Engineering Technology Professionals of Alberta (ASET).

What’s more, it could make a difference not just abroad, but in Canada.

A signal from the sky

After previously working with NAIT’s Alternative Energy Technology students to install solar energy systems in Guatemala and Peru, LUTW returned with the new request in fall of 2020.

After previously working with NAIT’s Alternative Energy Technology students to install solar energy systems in Guatemala and Peru, LUTW returned with the new request in fall of 2020.

“With the advent and increased development of lower-Earth-orbit, high-speed internet, we wanted to see what would be required to install a Starlink modem in a remote community in Peru, for example,” says Lytle, an engineer who retired as LUTW executive director in January 2022.

In areas too far from bigger cities for internet providers to reach with underground cable, consumers can get a signal from the sky, specifically via Starlink. Satellites float 550 kilometres above the earth in a constellation that encircles the globe. You just need a modem to receive the signal and a power source to run the system.

That’s an oversimplification, of course – especially in regions where there isn’t ready power.

“The idea was to build a prototype that could be dropped in anywhere.”

“The idea was to build a prototype that could be dropped in anywhere,” says Kevin Jacobson, chair of Wireless Systems Engineering Technology, which partnered with Alternative Energy Technology to address LUTW’s request. Also part of the idea was to offer a solution inexpensive enough for communities in the developing world.

“It’s solving a current problem,” Jacobson adds.

For the students who signed up to tackle that problem as part of the capstone project that rounded out their programs – including Natasha Bergstrom-Baier, Abdallah Farah and Jacob Maxwell (now alternative energy grads, 2021), and Steven Sager and Spencer Tracy (wireless systems grads, ’21) – the off-grid nature of the project would present one major challenge.

Another was the pandemic.

From Edmonton to Peru

In previous virus-free times, NAIT students would go abroad for such a project, getting on the ground to install solar-powered lighting, for example, so businesses can stay open after dark and kids can finish homework without having to endure fumes from a kerosene lamp.

In previous virus-free times, NAIT students would go abroad for such a project, getting on the ground to install solar-powered lighting, for example, so businesses can stay open after dark and kids can finish homework without having to endure fumes from a kerosene lamp.

With travel curtailed by the pandemic – and a shortage of Starlink modems that kept the group from getting one – data bridged the distance between Edmonton and rural Peru.

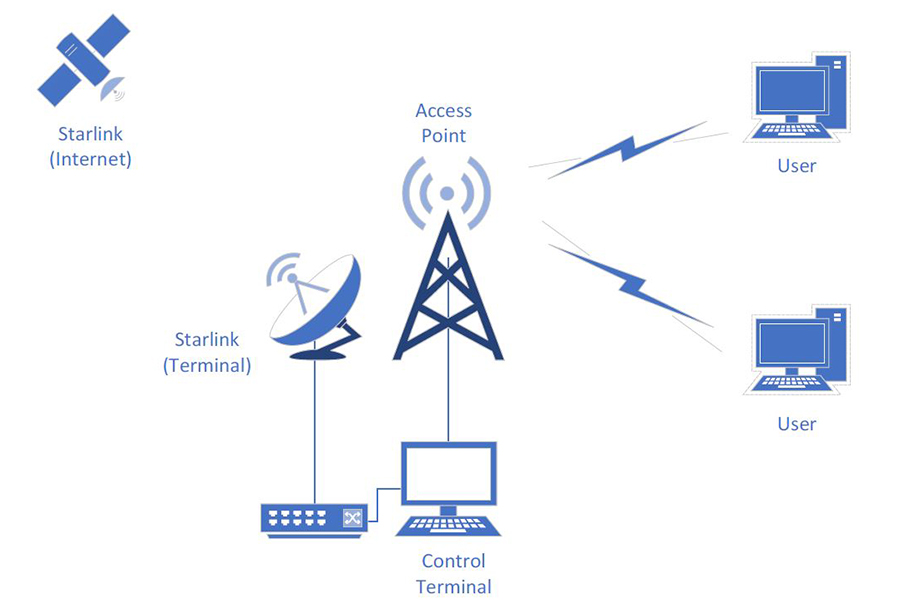

To determine the potential impact of their system, which would receive a signal from a satellite and then desseminate it via a land-based wireless internet service device (see the diagram above), Sager contacted Starlink users on Reddit who shared stats such as download and upload speeds.

“From basic calculations we were able to determine that we could provide internet to at least 50 or 60 people,” says Sager.

At slower speeds, he adds, the system could reach as many as 300 to 600 people.

Using simulation software, the alternative energy team determined the right mix of solar modules and battery power to ensure internet access throughout the day and part of the evening. The needs would not be great, it turned out, amounting to a power draw similar to two 60-watt incandescent bulbs, says Maxwell, who served as project lead.

Despite the relative simplicity of their system, the cost came in at $7,000 to $10,000 – a significant amount, given that just over 20% of Peruvians live in poverty, with rural areas being disproportionately affected.

“Our thought was that hopefully this would be affordable by the average agrarian Peruvian living off-grid in Peru,” says Lytle. “It became apparent that that just wasn’t going to work.”

Here, too, however, the students offered a solution: turn off-grid internet access into a business. “A person in that community can buy the equipment and break out the signal and sell it to their friends and neighbours,” says Lytle. LUTW, he adds, could microfinance the purchase.

“We thought that’s wonderful, because if we want this to proliferate throughout the world, this is the way to do it.”

Connecting Canadians

“I believe the greatest satisfaction will come when this project is on the ground and changing lives,” says Maxwell, who’s now at Lethbridge College for a certificate in wind turbine technology.

“I believe the greatest satisfaction will come when this project is on the ground and changing lives,” says Maxwell, who’s now at Lethbridge College for a certificate in wind turbine technology.

Sager is also back to school, at the University of Alberta for an engineering degree. He looks back on the NAIT project proudly. “I thought it was something that we could change the world with,” he says, “because having internet access will change somebody’s life.

“Having more access to information can allow them to develop their skills and knowledge to benefit their community, especially in parts of the world where it’s difficult to get that information.”

Or here in Canada. The team’s work is now informing another capstone project at Muskeg Lake Cree Nation. Roughly 80 minutes’ east of North Battleford, Saskatchewan, the community isn’t off-grid, but it needs reliable, high-speed internet. A new group of wireless systems students will help with the design and implementation of a Starlink system, leaning on the findings of their award-winning predecessors.

“They proved that it’s possible,” says Jacobson.

“I thought it was something that we could change the world with.”

They may have also proven that a lack of internet connectivity is a problem that communities can begin to solve for themselves – while they wait for governments to address the issue more broadly, which they’ve been spurred to do by the pandemic.

“We need to ensure that every Albertan, regardless of where they live, has the chance to participate in that future digital economy,” Premier Jason Kenney said during an announcement of a $390-million investment in broadband for Indigenous and rural communities where some 489,000 Albertans live.

By 2027, the project is expected to connect all homes and businesses to reliable high-speed, boosting the provincial GDP by as much as $1.7 billion as a result.

As the pandemic has shown, five more years is a long time to continue to be excluded from the digital economy, educational opportunities and more. In the meantime, students eager to develop their skills and do some good may have an answer.

“We’re standing on the shoulders of giants with the newly available technologies that have been offered to us,” says Maxwell. “In this capstone, we got to say, ‘OK, what’s the latest and greatest? What can we do when we put these pieces together, and how can that help people?’”

Along the way, they proved not only the technology, but they proved themselves as well.

“I would put this team up against anybody else I've ever worked with,” says Lytle. “They were able to open my mind up to things I would not have considered.”

What’s a “technologist”?

As Alternative Energy Technology grad Jacob Maxwell describes, technologists create real, functional solutions for current market needs. They bring engineering designs to life.

“The contribution that technologists make everyday is really significant,” says Barry Cavanaugh, chief executive officer of ASET, the Association of Science and Engineering Technology Professionals of Alberta. Cavanaugh defines them as “practical engineers,” in the sense that their work is hands-on in fields ranging from architecture to welding.

ASET’s annual capstone project of the year award highlights student innovation in addressing real-world problems. As such, it highlights the quality of education at Alberta’s post-secondary institutes and their impact, through students and instructors, on the community.

With respect to the success of the five Alternative Energy Technology and Wireless Systems Engineering Technology students who won the 2020-21 award for their sustainable satellite internet system, the award “really shines a light on NAIT and what it’s doing – producing people of great utility to society,” says Cavanaugh.