Efforts shine a light on an often overlooked aspect of province’s past

When asked where she’s from, Deborah Beaver tends to be inexact – but only to be practical.

“Nobody really knows where Campsie is,” she says of the hamlet where she grew up.

But just east of that tiny farming community is Barrhead, so Beaver goes with that. With a population of just over 4,700, it’s big enough to be familiar to many in northern Alberta.

But just east of that tiny farming community is Barrhead, so Beaver goes with that. With a population of just over 4,700, it’s big enough to be familiar to many in northern Alberta.

That habit could be about to change, as Beaver may be better positioned than ever to bring Campsie the recognition it deserves.

Thanks to recent efforts of NAIT students, she’s shining a brighter light on the history of her hometown and on other communities that were settlements for Black people who sought refuge from racism in the United States in the early 20th century.

It’s a story that Beaver, as a descendant of those settlers and cofounder of the Black Settlers of Alberta and Saskatchewan Historical Society (BSAS), feels has gone overlooked to the disadvantage of all communities, Black or not.

“Black people have been here for more than 100 years,” she says.

“There are just so many people who don’t know.”

Preserving a shared past

Beaver and three other cofounders launched BSAS as a society nearly two decades ago. In 2005, she worked at the University of Alberta drama department, where she connected with the writer of a play called Ribbon set in Amber Valley, another northern Alberta community settled by Black Americans.

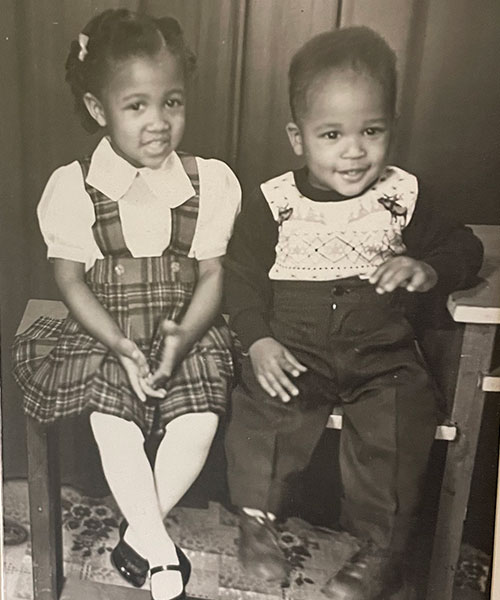

To support the work, writer Pat Darbasie wanted to gather historical photos, a job Beaver assigned to a student. Surprised by the audience’s appreciation of those visuals, Beaver realized she could help meet a desire to resurface an all-but-forgotten past. BSAS formed soon after to gather and preserve images and conduct video interviews with aging descendants.

“Now it’s taken on a life of its own,” says Beaver.

Part of that has played out at NAIT, where Bachelor of Technology instructor David Schmaus, also from Campsie, knew of Beaver’s project and reached out about collaborating. By January 2023, she was working with a team of Digital Media and IT students – Karla Hamilton-Oteiza, Elhan Yusuf and Gurkomal Singh (now class of ’23 grads) – on a new BSAS website.

At the same time, other students started setting the stage for Beaver’s other wish: a documentary on Campsie and Wildwood, another Alberta Black settlement. Braelyn Bogdanov (Interior Design Technology ’21), Paul Cadrain (DMIT ’21) and Baljinder Kumarji, as part of earning their BTech degrees, prepared source materials by digitizing interviews, timestamping topics they covered, coordinating with provincial archivists and more.

Their work wrapped up in August. In addition to honing project management skills, Bogdanov and Cadrain point to deeper learnings.

Their work wrapped up in August. In addition to honing project management skills, Bogdanov and Cadrain point to deeper learnings.

“Going into this, we were not very aware of Black history in Alberta,” says Cadrain.

That meant learning about the settlers themselves, but also about struggles that stemmed from racism in their new home.

“The land that they were offered was really quite poor,” says Cadrain.

That those early settlers stuck it out has changed Bogdanov’s perspective on Alberta. How might the province look today had those farmers not arrived from the likes of Oklahoma and Texas to break hard land and build communities around it?

“It might not have been settled,” Bogdanov speculates – at least certainly not in the same way.

That, she adds, might alter the diversity of her community as she now knows it. For example, while sorting through photos for BSAS, Bogdanov noticed that one bore the surname of a coworker. She asked if there was any connection.

“I'm really happy that I got to be a part of preserving such important history.”

Bogdanov’s colleague was stunned. “That's my great grandfather!” she said. “Where did you get this?”

For Bogdanov, of Eastern European descent, the coincidence confirmed that modern Alberta communities owe themselves to a past shared by those of more than one culture.

“I'm really happy that I got to be a part of preserving such important history,” she says. “I learned a lot about … my home and where I live.”

Cadrain hopes their project for BSAS has a similar impact on others.

“If I can see things that drew on our work years from now, I think that [will be] humbling.”

Continued learning, continued collaboration

Already, that may be coming to pass.

Already, that may be coming to pass.

Recently, Donovan Hayden, a Black activist and theater creator from Toronto, visited Campsie with Beaver for research for a play about an immigrant from the American south to the Canadian west in the early 20th century.

For Hayden, the story of that settlement shows the depth of Black history across Canada, not just in places like Toronto and Nova Scotia.

“That doesn't get a lot of attention,” he says.

Were the story better known, Hayden feels it could help reinforce the fact that, “as a Black person, you do belong here, you do have this deep history here, and you should be proud of that.”

To help bring characters to life, the playwright spent time on the BSAS website studying faces, clothes, activities, surroundings and more to inform a story about facing a harsh environment and, often, a harsh reception. He hopes that helps broaden his audiences’ understanding of Canada.

“I think the value of these websites is that it gives someone like myself, who [is] learning the history, somewhere to actually go and see [it],” says Hayden.

“And that's why I really respect people like Debbie. They don't know if that will ever happen – if some playwright from Toronto will come across their website and get in contact. But they still do it with the hope that this history will continue to be learned by everyone.”

Now matched with a new group of NAIT students, Beaver will continue those efforts by moving closer to producing a documentary.

The irony of tightening the focus on those settlers from a century ago isn’t lost on Beaver. When her grandparents arrived in Alberta, they didn’t seek attention. Instead, she says, they tried to “melt in” so that they might live peacefully, build communities and grow them.

But singling them out now, and making Campsie a name as familiar as that of any other Alberta town, might also contribute to community building, strengthening connections between places and people, and perhaps each other.

“They are not people who would have been looking for any recognition,” says Beaver of Alberta’s Black settlers. “And now they’re being recognized. It does give me a sense of pride.”